Prominence formation by levitation-condensation at extreme resolutions Author: Jack Jenkins

As the ERC PROMINENT project suggests, a primary aim is to understand where, how, and why prominences form within the solar corona - the atmosphere of our nearest star the Sun. Historically speaking, solar prominences - their origins and properties - have been studied observationally using telescopes, be them on the ground, near-Earth orbit, or elsewhere in the heliosphere. This has taught and continues to teach us a great many things. Unfortunately, throughout much of this history the corresponding numerical simulations of solar prominences have been unable to rival such resolutions. This was frustrating for a long time as although observations provide us with the context and bounds of our simulations, their own diagnostic limitations often prevent them from truly exploring the small-scale physics present. Observations provide us with two quantities, intensity and polarisation, and neither are a direct measure of, say, density, temperature, or magnetic field strength. In order to obtain such quantities, complicated models are often employed that range in their assumptions and limitations. Numerical simulations, however, contain such quantities as base components and so we know the density, temperature, and magnetic field strength throughout our entire simulation domain at any given time - of course I’m not trying to say that numerical simulations are infallible, they have limitations of their own. Nevertheless, with the advances in computing technology, numerical simulations carried out within the last decade have been catching up and are commonly able to capture the structure and dynamics of solar prominences at a scale equal to that of observations. Now, with the upcoming Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope (DKIST), this resolution goalpost is trying to leave numerical simulations behind once more.

The MPI-AMRVAC code (Message Passing Interface - Adaptive Mesh Refinement Versatile Advection Code) is a modern and open-source numerical simulation toolkit that solves the Magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) equations. Developed at the Centre for mathematical Plasma Astrophysics at KU Leuven, Belgium, the core team of developers has been working hard to expand the functionality of the code so as to benefit from the state-of-the-art, parallelised computing architecture available at tier-2 and tier-1 computing facilities such as the Vlaams Supercomputer Centrum (VSC). It is through these advances that we are able to present to the scientific community, and you - the reader, results of the first big step in our goal to realise the formation and evolution of prominence condensations within ERC PROMINENT at a mind-blowing resolution of approximately 5.6 km - the same order of magnitude as will be possible with DKIST (0.011” => 8 km).

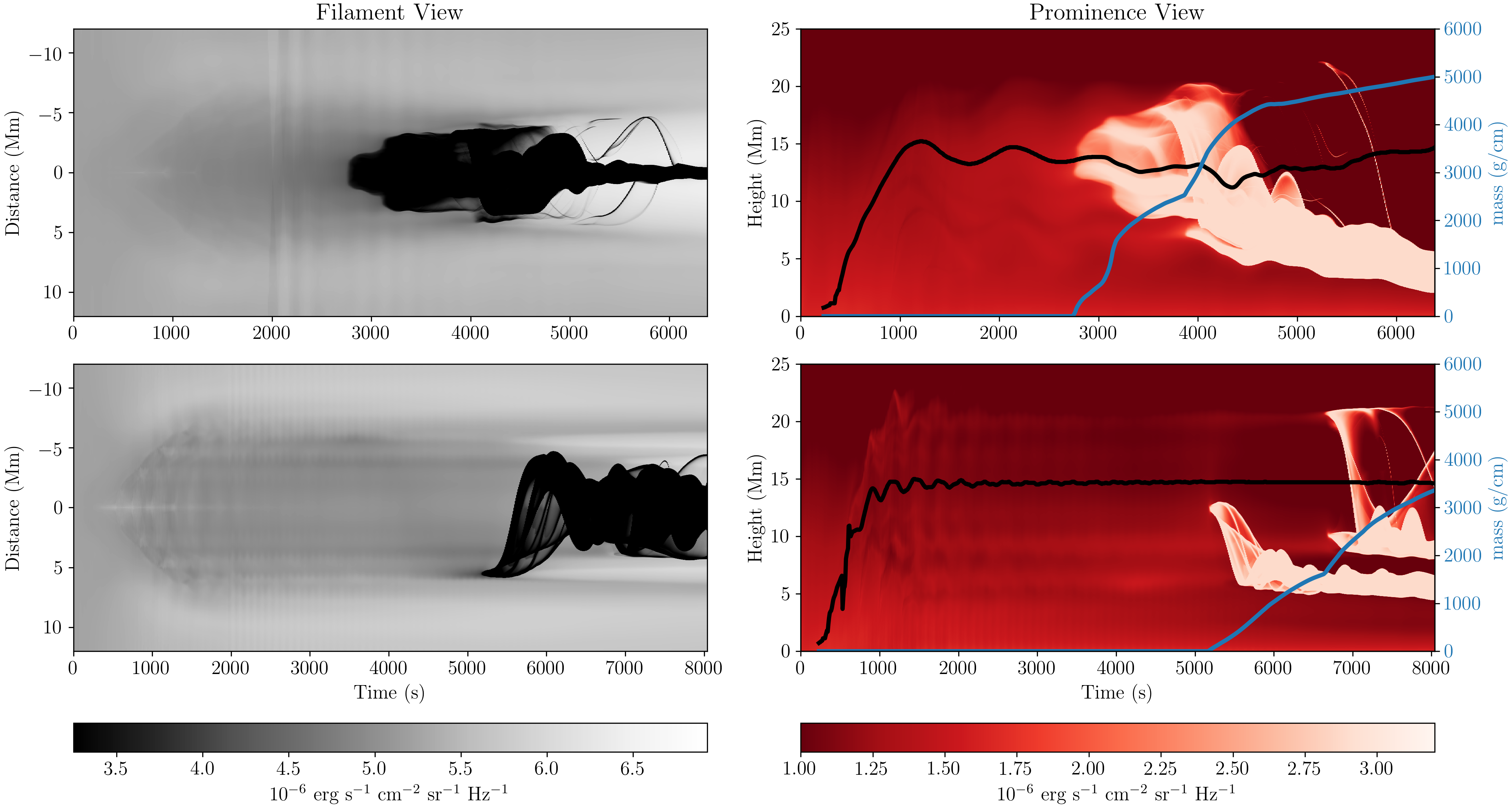

In order to obtain such a resolution, the setup of this particular simulation is 2.5D i.e., 2D with constant properties (invariance) in the 3rd dimension. Of course, the real world has three spatial dimensions but this simplified approach serves as a good starting point for testing the setup, evolutions, and post-processing that will later be transferred to full 3D. Without going into too much detail, the magnetic structure that is commonly believed to host solar prominences - a magnetic flux rope - is in this instance oriented such that the axis of the structure is perpendicular to the 2.5D plane, meaning the simulated flux rope is infinitely long in the invariant direction. After the initial condition of a linear force-free magnetic topology is deformed so as to create this flux rope via magnetic reconnection, cool condensations form spontaneously within the magnetic rope that subsequently evolve under gravity towards the solar surface. Depending on the strength of the magnetic field within the flux rope - the 3 Gauss case referring to ‘quieter’ conditions than the 10 Gauss (3G & 10G, respectively) - we find different but generally similar behaviour between the aforementioned post formation condensations. And finally we demonstrate what this evolution would look like if synthesised to appear in the famous Hydrogen-α spectral line core (see the banner of this page).

The first step in creating a full 3D prominence formation and condensation model with MPI-AMRVAC was successfully completed in Jenkins & Keppens (2021) with a 2.5D translationally-invariant setup. This study revealed a range of dynamics and instabilities at work during the onset of condensation formation within a prominence - the specifics of which can be read in detail here. A selection of the movies that accompanied that paper are reproduced here.